Overview

Sweden is located on the Scandinavian peninsula, surrounded by the Baltic Sea to the south and the east and by the North Sea to the south-west. It is a comparatively sparsely populated country (25.7 inhabitants per km2 on average) and covers an area of almost 532,000 km2, of which 122,000 km2 is inland waters. This makes Sweden the third largest country in the EU and the fifth largest in Europe. From north to south it spans a maximum length of 1,572 km and is 499 km at its widest. In total, Sweden had almost 10.5 million inhabitants at the end of 2021. More than 100,000 people live in 19 of the country’s 290 municipalities; only four municipalities have more than 200,000 inhabitants, namely Uppsala (237,596), Malmö (351,749), Gothenburg (587,549), and the capital city of Stockholm (978,770) (SCB 2022).

Sweden is bordered by Norway to the west, Finland to the east, and Denmark to the south. The country encompasses almost 100,000 lakes and nearly 270,000 islands (38% of which are surrounded by seawater), with Gotland and Öland being the largest islands with almost 300,000 ha and 135,000 ha respectively. Waters comprise 23% of Swedish territory, which is mainly characterised by forest (52.4%); built-up areas and developed land make up only 2.4% of the country. It is also noteworthy that 12.8% of the overall land area comprises protected nature areas (national parks, nature reserves, Natura 2000 sites, etc.) and 61% is ‘envisaged’ as potential reindeer grazing land, although this also includes water areas (SCB 2019).

The country is home to five national minorities and their languages, which were officially recognised in 2000 in connection with Sweden’s ratification of the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. These are the Sami and the Sami language, the Swedish Finns and Finnish, the Tornedalers and Meänkieli (sometimes called Torne Valley Finnish), Jews and Yiddish, and finally, the Roma and Romani Chib, which together comprise around 10% of the national population. As of the end of 2021, 20% of the Swedish population was born outside of Sweden and 8.4% hold foreign citizenship (SCB 2022).

Sweden is a parliamentary democracy. Its parliament has 349 members in a single chamber. The government’s role is to implement the decisions of parliament and to formulate new laws or amendments to laws on which parliament then votes. The aforementioned indigenous Sami people have their own parliament, the Sametinget. It is both an elected parliament and a public agency. The agency’s main task is to act for the living Sami culture, which includes in particular reindeer husbandry and preserving the Sami language. Sweden is also a constitutional monarchy, which means that the monarch is Sweden's non-political head of state with primarily ceremonial and representative duties.

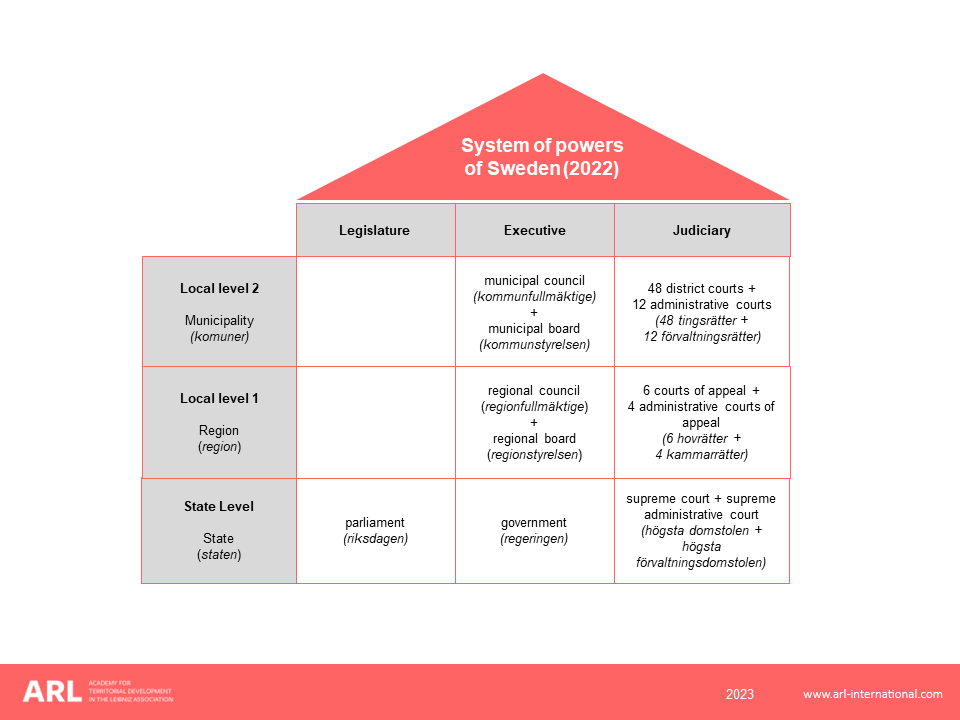

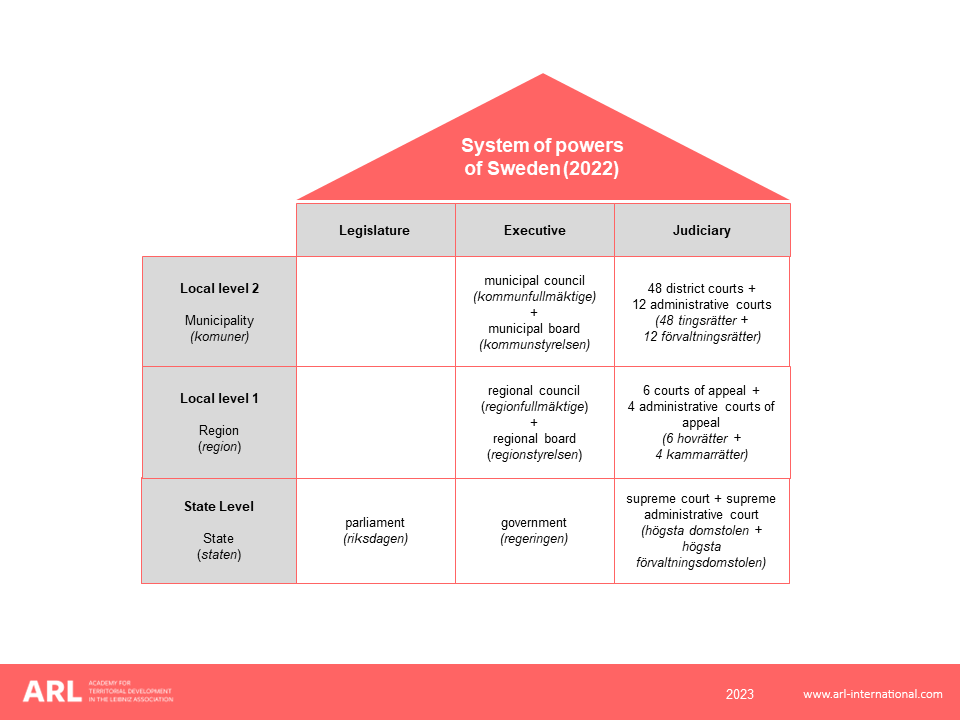

Overall, Sweden can be characterised as a unitary state in which the central government delegates authority within a three-tier structure of government: central, regional, and municipal. In total, there are 21 regions (regioner, before 2019 called landsting), and 290 municipalities (kommuner), (see figure 1).

The island of Gotland is a municipality which also carries out the responsibilities of a regional council. Regions and municipalities do not hold legislative powers; nonetheless, they do have executive powers in taxation and administration at their respective levels. The members of the two levels of self-government (regional and municipal) are elected in local and regional elections every fourth year on the same date as the national elections. In principle, there is no hierarchy between these two levels of self‑government, just different areas of responsibilities. Therefore, they are designated as local level 1 and local level 2 in figure 1 and in figure 2.

In 1995, Sweden joined the EU based on a national referendum held the year before. An additional referendum in 2003 on the introduction of the euro was rejected. It is also noteworthy that Sweden, together with Finland, applied as late as 2022 to become a member of NATO, whereas the other three Nordic countries – Denmark, Iceland, and Norway – have been NATO members since its foundation in 1949. On the other hand, Norway and Iceland are (still) not EU members, whereas Denmark joined the EU back in 1973 and Finland, together with Sweden, in 1995. All five Nordic countries can draw upon a long history of collaboration within the Nordic Council of Ministers in a number of different policy areas, such as energy, research, digitalisation, environmental issues, youth and cultural policy.

General information

| Name of country | Sweden |

| Capital, population of the capital (2020) | Stockholm, 975,551 (Statistikmyndigheten) |

| Surface area | 528,860 km² (World Bank) |

| Total population (2020) | 10,353,442 (World Bank) |

| Population growth rate (2010-2020) | 10.40% (World Bank) |

| Population density (2020) | 25.4 inhabitants/km² (World Bank) |

| Degree of urbanisation (2015) | 29.16% (European Commission) |

| Human development index (2021) | 0.947 (Human Development Reports) |

| GDP (2019) | EUR 452,863 million (World Bank) |

| GDP per capita (2019) | EUR 44,057 (World Bank) |

| GDP growth (2014-2019) | 17.00% (World Bank) |

| Unemployment rate (2019) | 6.83% (World Bank) |

| Land use (2018) | 1.53% built-up land 8.84% agricultural land 65.60% forests and shrubland 9.07% nature 14.97% inland waters (European Environment Agency) |

| Sectoral structure (2017) | 65.4% services and administration 33.0% industry and contruction 1.6% agriculture and forestry (Central Intelligence Agency) |

To ensure comparability between all Country Profiles, the tables were prepared by the ARL.

Administrative structure and system of governance

Sweden is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy. This means that the national parliament, the Riksdag, is the foremost representative of the people. Sweden has four constitutions: The first is the instrument of government (regeringsformen), which stipulates how the country is to be governed and how democratic rights are to be maintained. The other three constitutions are the Act of Succession, which rules on who shall succeed to the throne, the Freedom of the Press Act, and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression. Although written rules determining how the country is to be governed have existed since the 14th century, a parliamentary system was only set up after the end of the First World War and introduced into the constitution as late as in 1969. The power of the monarchy in Sweden diminished over the years, while parliamentary democracy was strengthened. In 1809, an Instrument of Government was enacted which ruled on the division of power between the monarch and the national parliament. Since 1974, when the current Instrument of Government came into force, the monarch has had only ceremonial and representative duties and functions as Sweden’s non-political head of state.

The prime minister is appointed by parliament, and the prime minister in turn appoints the 23 ministers that work within 11 different ministries in the government which was formed in autumn 2022. For instance, currently two ministers are heading the Ministry of Infrastructure: one which is responsible for Rural Affairs and one for Infrastructure and Housing. The latter is also responsible for spatial planning and transport issues. In recent years, the Swedish government has often been formed by minority coalitions or one-party governments that needed to seek support from other parties.

Elections to parliament are held every four years on the second Sunday in September. Parliament today has a single chamber of 349 members, who are elected by proportional representation. The general threshold for any one party to be allocated a seat in parliament is that they must receive at least 4% of the votes. Eight parties currently have seats in parliament.

One of parliament’s main tasks is to make laws. Usually, the government proposes new laws, or amendments to current laws, in the form of government bills (propositioner). In addition, one or several members of parliament can submit proposals (motioner). Similar to a government bill, every proposal is further discussed in one of the 15 parliamentary committees (utskotten) that have different sectoral responsibilities (e.g. Transport and Communications, Environment and Agriculture). In addition, parliament takes decisions on the expenditures and revenues of the central government budget and examines the work of the government and of the 400+ national public agencies (myndigheter) in Sweden.

Sweden can be characterised as a unitary and decentralised state in which the central government delegates authority within a three-tier governmental structure: central, regional, and municipal (see figure 1). As mentioned above, parliament has legislative power, but also controls financial issues and the government’s work. The government itself is accountable for the decisions taken. However, the ministries can only be made accountable for a few decisions, since Sweden does not follow a ministerial tradition (such as in Denmark and Norway), in which ministers can, for instance, overrule public agencies. Instead, Sweden follows a technocratic tradition, which is characterised by small ministries with limited mandates and no executive power. This also means that the 400+ national public agencies are relatively autonomous, since the national government has no power to intervene in an agency’s decisions relating to the application of the law or to intervene directly in an agency’s day-to-day operations. In other words, the public agencies decide and implement matters under their authority. Collective government decision-making and the ban on instructing agencies on individual matters reflect the prohibition of the ‘ministerial rule’, which is overseen and ensured by parliament.

Local self-government is one of the most important democratic principles in Sweden. As mentioned above, from a legal perspective, regions and municipalities are deemed to be similar – they are both regulated through the Local Government Act (kommunallagen). Hence, in legal terms Sweden has 310 local administrations, which include the 290 municipalities and the 21 regions, while the island of Gotland is both a region and a municipality.

Figure 1: Administrative structure of Sweden

In the 21 Swedish regions, people vote for the members of the regional council (regionfullmäktige), which elects the regional board (regionstyrelsen). Similarly, at the municipal level, people vote for the members of the municipal council (kommunfullmäktige), which elects the municipal board (kommunstyrelsen) (see figure 2).

Figure 2: System of powers of Sweden

The Swedish legal system has a three-tier structure with two different types of court (domstolar), namely general courts (allmänna domstolar) and administrative courts (förvaltningsdomstolar). The general courts are divided into 48 district courts (tingsrätten), six courts of appeal (hovrätten) and one supreme court (högsta domstolen), whereas the administrative courts are divided into 12 so-called förvaltningrätter, four kammarrätter, and one supreme administrative court (högsta förvaltningsdomstolen). In other words, the general and administrative courts do not correspond geographically or institutionally to the prevailing territorial-administrative jurisdictions in Sweden (see attachment 1 and figure 2).

The five land and environmental courts in Sweden are part of the general courts and decide on cases that relate to real estate, environmental issues, planning and construction as well as water and sewage. The district court is the court of first instance in a case. If the prosecutor or defender in a case is not satisfied with the district court’s ruling, the case goes to the court of appeal. The supreme court selects cases that are appealed from the court of appeal. The cases raised are those that are considered to be precedent-setting (indicative) and form the basis for future legal interpretations. The administrative courts rule on cases of public law, which applies to matters between the state, region, or municipality and the individual citizen (including building permits). The principles of which cases are brought before the various instances are the same as for the general courts.

Regions and municipalities do not hold legislative powers, but they do have executive powers in taxation and administration at their respective levels. Taxes are levied as a percentage of the inhabitants’ income, with an overall local tax rate of around 30%, of which around 20% goes to the municipality and 10% to the region. In addition, as in many other countries, a financial equalisation system exists to balance out economic differences between different regions and municipalities across the country. These local administrations, i.e. the regions and municipalities, are also financed by government grants (e.g. for transport infrastructure) and fees paid by local residents for various services.

Although legally there is no difference between municipalities and regions, they hold different responsibilities. The regions have responsibility for public health (including

healthcare and medical services), cultural institutions, and public transport (often shared with the municipalities). Since 2017, all 21 regions have been in charge of regional development (regional utveckling) and are supposed to develop regional development strategies (regionala utvecklingsstrategier, RUS). Only three of the 21 regions (Stockholm, Skåne, and Halland) have a formal mandate to undertake regional planning according to the Planning and Building Act (see below). Municipalities hold mandatory administrative powers in the fields of transport (including local roads), social welfare, education (schools), the emergency and rescue services, health protection, the environment (including environmental protection, refuse and waste management, water and sewage), housing as well as planning and building issues. Further municipal responsibilities on a voluntary basis are leisure activities, culture, energy, industrial and commercial services, employment, and tourism.

In each region, the national state administration has installed a county administrative board (länstyrelse), which (still) carries the historical Swedish term län (counties in English). Each county administrative board is headed by a governor (landshövding) appointed by the government. The county administrative boards must work to ensure that national goals are secured in the regions (e.g. concerning land-use planning), while taking regional conditions into account. County administrative boards also coordinate different policy areas, such as ecosystem services, crisis management, nature protection, cultural heritage, transport, and infrastructure. They also review comprehensive and detailed municipal plans as well as regional plans and regional development strategies (see below).

In conclusion, Sweden can be characterised as a non-federalised political system, but with a strong tendency to decentralise administrative as well as (for the most part) political powers to local administrations, i.e. the regions and municipalities. However, in many policy areas, such as spatial planning, municipalities are in a much stronger position than the regions. Nonetheless, these local administrations are controlled by the national state and its institutions. The county administrative boards as well as a number of national public agencies are of particular interest here, as some of them play a crucial role in guiding different aspects of spatial planning (see below).

Spatial planning system

Historical development

Similar to other European countries, the first public planning efforts based on statutory instruments (e.g. grid plans and master plans for smaller areas) can be traced back to the second half of the 19th century, with the aim of improving sanitation standards and the build quality of wooden houses. The first milestone in terms of further formalising spatial planning was the Town Planning Act of 1907 (stadsplanelag), which introduced the first type of comprehensive plan for entire municipalities, which was intended to regulate basic land-use issues (i.e. to indicate areas for buildings and for public places).

Sweden was spared destruction and occupation during the Second World War and thus was not held back in its societal and socio-economic development as most other European countries were. Therefore, as early as the 1930s, the Swedish welfare state and in particular the overarching political ideal of what was called the ‘people’s home’ (folkhemmet) gradually evolved, in which modern spatial planning played a central role (Strömgren 2007). Across society, there was a clear consensus that public planning was a key tool in creating a home for all people based on equality and a broad political consensus. In the Swedish welfare state housing has played a central role, not least because of the process of industrialisation after the Second World War, and the subsequent growing demand for modern and affordable housing. This culminated in the so-called One Million Homes Programme, a public housing programme implemented between 1965 and 1974. In the heyday of the welfare state the term samhällsplanering was coined, with samhälle meaning society / Gesellschaft / société. However, the Swedish term also encompasses the notion of community as well as of settlement, village, town, or suburb and thus also has a physical and spatial dimension (Bohm 1996). Overall, samhällsplanering is a professional term, often used in educational programmes as well as for job titles, but which is not used in legal frameworks. In practice, it often includes many different types of planning and as such is fairly close to the use of the EU English term spatial planning (Schmitt/Smas 2018). The term samhällsplanering also appears in the name of the Swedish Planning Association (Föreningen för Samhällsplanering), which was established in 1947.

The year of the foundation of this association is not a coincidence, as it is a crucial date in Swedish planning history. In 1947, a new building act (byggnadsstadga) was adopted that introduced a more advanced form of what can be called general municipal plans (generalplaner) compared to those enacted by the Town Planning Act of 1907. This building act was renewed in 1959, which resulted in more power being shifted to the municipalities to control and develop the use of land and water.

The Swedish Act for Nature was adopted in 1964, which introduced the provision for nature reserves and for shore protection. In the same year, a national agency for planning and natural resources (statens planverk) was founded, followed by the environmental protection agency three years later. In 1972, another institution was set up for what could be translated as national physical planning (fysisk riksplanering). This type of planning had little to do with the comprehensive planning approach to guide land-use planning and settlement structures, which was desired by radical architects and socialists back in the 1940s. Instead, national physical planning aimed to protect natural and environmental resources as well as to preserve strategic resources (Strömgren 2007: 143). The term ‘national physical planning’ is also misleading, since the agency’s focus was on the inventorisation and documentation of natural resources, which subsequently laid the basis for the ‘areas of national interest’ planning instrument (områden av riksintresse, see below) as stipulated in the Natural Resources Act (naturresurslagen) in 1987.

In the 1980s, it was increasingly recognised that the legislation that guided planning and building activities was fragmented and the status of various planning instruments was unclear. Similarly, according to Nilsson (2018), the need for long-term management of land and water increased, which led to the enforcement of an entirely new Planning and Building Act (plan- och bygglag) in 1987. This new act strengthened the coordination of different interests and conflicts, improved citizen participation and clarified the responsibilities of the state, the municipalities, and other actors. The established instruments since 1947, such as general municipal plans (generalplaner) as well as detailed plans within planning areas (stadsplaner) and detailed plans outside planning areas (byggnads planer), were replaced by comprehensive plans (översiktsplaner) and detailed plans (detaljplaner), which are still the two most important municipal statutory planning instruments (see below). Also, since 1987 each municipality must have a valid comprehensive plan for the entire municipal territory laying out the intended use of land and water as well as how the plan relates to areas of national interest as defined in the Natural Resources Act. Two years later, in 1989, the National Board of Housing and Planning (boverket) was founded by merging the previous National Board of Building and the National Board of Planning.

In 1999, the 15 existing environmental acts were merged into one Environmental Code (miljöbalken), with the overall aim to provide more stringent environmental legislation and to better promote sustainable development. In the same year, the Swedish Parliament also decided to establish 16 environmental quality objectives to be integrated into the municipal planning process, such as reduced climate impact, flourishing lakes and streams, flourishing coastal areas and archipelagos, thriving wetlands, sustainable forests, a varied agricultural landscape, a good built environment, and a rich diversity of plants and animal life (Nilsson 2018: 131).

In the 2000s and 2010s, a number of adjustments were introduced to the Planning and Building Act in order to make planning simpler, faster (e.g. in order to be more responsive to the ongoing housing shortage), and more sustainable. These sought to reduce unnecessary duplications of reviews, increase opportunities to build without planning permission and demand that the environmental and climate impacts of planning and building activities are properly taken into account.

This brief historical journey underscores that Swedish spatial planning today is basically characterised by what is known in the Swedish context as the municipal planning monopoly (kommunalt planmonopol). In other words, the national state provides legal frameworks (here: the Planning and Building Act and the Environmental Code) and various policy programmes (e.g. to promote sustainable urban development or to speed up house building), but otherwise is not allowed to interfere in municipal planning affairs. This also means that statutory-based ‘regional physical planning’, which corresponds to the Swedish legal term regional fysisk planering, has a rather weak position according to the Planning and Building Act. It is also noteworthy that regional physical planning is only legally formalised in the Planning and Building Act for three of the 21 regions, namely for the Stockholm region (since 1947, with the first regional plan adopted in 1958), for the Skåne region (since 2019, with the first regional plan adopted in 2022), and for the Halland region (since 2023, the work on the first regional plan has just started).

Historically, different forms of regional planning existed and still exist, in other Swedish regions as well. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the national state created regional planning associations. Later, in the preparatory work for the Planning and Building Act of 1987, it was argued that regional planning did not work particularly well and there was no longer a specific need for such a state-run regional planning approach due to the documentary and inventory work undertaken within physical national planning (fysisk riksplanering, see above). In addition, two larger territorial reforms reduced the need for intermunicipal coordination (in 1952, the 2,400 municipalities were merged into 800 and then in 1974 finally into 284). Today (in early 2023), Sweden has 290 municipalities, many of which are larger than planning regions in many European countries in terms of surface area, which underscores that municipal planning inevitably often takes into consideration issues which are of regional scope, such as urban-rural interactions, technical and social infrastructure provision, and ecosystem services. The specific spatial planning situation at the regional level will be further discussed below.

Spatial planning authorities, instruments, and coordination

National level

After the national election in September 2022, the responsibility for spatial planning (samhällsplanering) shifted from the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (näringsdepartementet) to the Ministry for Infrastructure and Housing (infrastrukturdepartementet). According to the Planning and Building Act, the national government has the decision-making power to entrust planning to a regional planning body as well as to define areas of national interest (områden av riksintresse) according to the Environmental Code, which will be further discussed below. In addition, the government can submit government bills (propositioner) for legal adjustments or establish policies to promote house building and new transport infrastructure, for instance. In addition, the national government can steer the strategic operations of public agencies, such as the National Board of Housing, Building, and Planning (boverket). However, as mentioned above, it has no powers to intervene in a public agency’s decisions in specific matters.

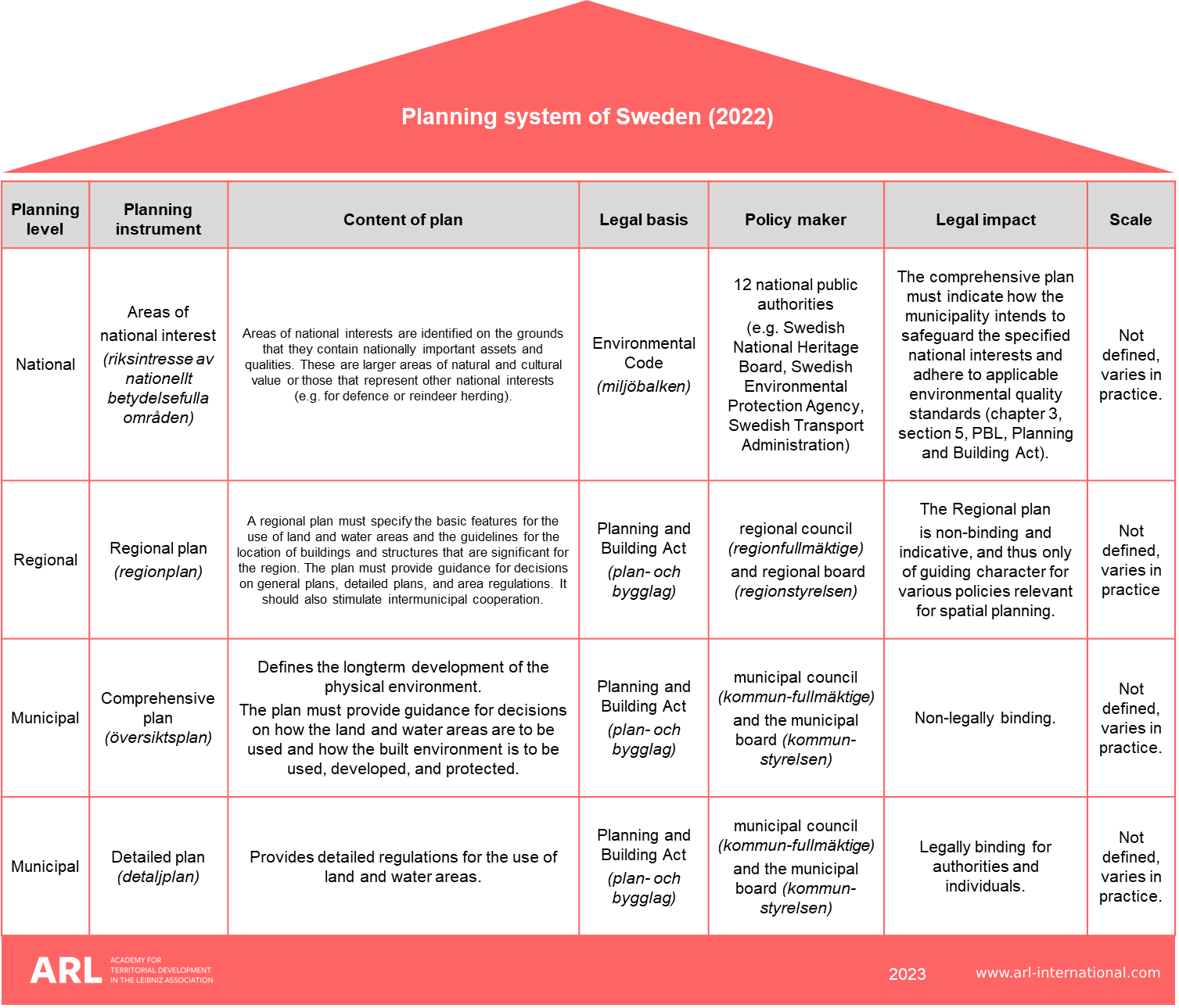

Areas of national interest (områden av riksintresse) are so identified because they contain nationally important assets, resources or qualities, which are to be safeguarded, either for protective or exploitative reasons. In other words, specific areas are designated in order to prioritise certain land uses or to safeguard their land-use potential, e.g. for conservation purposes or for commercial activities, such as fishing and reindeer herding. Since 1987, when this planning instrument was legally codified, these areas of national interest have been reviewed and other areas of national interest have been added, such as for energy production, marine resource use as well as for strategic infrastructures and industries. As such, this planning instrument represents collective goods, common-pool resources as well as economic and security interests (Solbär et al. 2019: 2149).

In the comprehensive plan, the municipality has to show how the areas of national interest are catered for within its territory and how these areas relate to other interests in the specific local context. Since the comprehensive municipal plans are controlled by the county administrative boards, which are administrations of the national state operating at the regional level, the national level can ensure the extent to which areas of national interest are actually safeguarded. There are two types of areas of national interest: a) areas of natural and cultural value, which are listed in the Environmental Code and as such comprise explicitly defined landscapes in their entirety (i.e. certain coasts, large islands, mountain areas, large riverine valleys, and sizeable inland waters) (Solbär et al. 2019); b) areas that are identified by the 12 national public agencies according to the Environmental Code (such as for geological reasons, e.g. unexploited mineral deposits, areas for the Sami people and their reindeer herding, or as areas for defence). The National Board of Housing, Building, and Planning (boverket) is responsible for the overall coordination of this planning instrument.

At the national planning level, the national infrastructure plan should be mentioned, which is proposed by national agencies such as the Swedish Transport Administration (trafikverket) and adopted by the national government. This plan is clearly an investment instrument, whereas the areas of national interest are a regulatory instrument. Overall, as in many other European countries, the coordination and integration of sectoral policy areas (such as energy, agricultural, and rural policy as well as regional/economic development policy) with spatial planning at the national level is rather modest, thus national spatial planning can be considered a separate system (see Schmitt/Smas 2020).

Hence, it is not surprising that there is no national spatial planning document, e.g. in the form of strategic guidelines, as for instance is regularly produced in Germany, Austria or Finland. Yet, some years ago, the National Board of Housing, Building, and Planning on behalf of the government produced a Vision for Sweden 2025 (Boverket 2012), which has been solely an inspirational report depicting different potential futures, rather than a strategic national planning document. Inspired by examples from other countries, a more recent initiative by the same national public agency proposed the establishment of a national advisory board to support the coordination of different public agencies in matters relevant for spatial planning as well as establishing a dialogue between different planning actors (e.g. the county administrative boards). This initiative was motivated by the growing complexity of ongoing transformation processes in a number of Swedish regions and municipalities (Boverket 2022).

Finally, following the EU directive on maritime spatial planning of 2014, this type of planning is regulated in the Environmental Code. The Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (Havs- och vattenmyndigheten) is the responsible national public agency that has prepared the three existing marine plans (for the Gulf of Bothnia, the Baltic Sea, and the Skagerrak/Kattegat) in collaboration with the neighbouring countries, which were adopted by the government (Havs- ochvattenmyndigheten 2022). As such, it is noteworthy that in Sweden a national cross-sectoral spatial planning approach does not exist ‘on land’, but does for the sea. This is also underlined by the sub-title of the planning document in which these three marine plans are published: State planning in the territorial sea and economic zone (Statlig planering i territorialhav och ekonomisk zon).

Regional level

As alluded to above, within the Swedish spatial planning system, the regional level is positioned rather weakly compared to the systems in many other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, France or Poland (Smas/Schmitt 2021). However, in recent decades, a number of public inquires and suggestions for reform have questioned the role and function of regions within the political administrative system in Sweden (e.g. SOU 2007: 10). Within this debate, ‘regional physical planning’ has been suggested as an important governance tool for housing provision and sustainable development (SOU 2015: 59). Yet, the institutional arrangements and conditions for regional planning differ between regions, and a number of governance experiments and different institutional set-ups for informal regional planning (i.e. not in accordance with the Planning and Building Act) have been developed (Schmitt/Smas 2019; Smas/Lidmo 2019; Smas/Schmitt 2022).

In general, one can discern a clear institutional divide between regional planning and regional development, which are governed by different legal frameworks and which have developed parallel communities of practice (Emmelin/Nilsson 2016). The former is regulated by the aforementioned Planning and Building Act and the latter by the Act on Regional Development and the regulations on regional growth work. The intention is to promote sector-wide cooperation between actors at local, regional, national, and international level, while economic, social ,and environmental sustainability must be an integral part of analyses, strategies, programmes, and efforts. Each of the 21 Swedish regions is responsible for its own regional growth work, which includes producing and implementing regional development strategies (regional utvecklingsstrategier), which are reviewed by the county administrative boards.

There are a number of examples where this institutional divide between regional planning and regional development is bridged in practice as reported by the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building, and Planning (Boverket 2017). Moreover, the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (tillväxtverket) is currently co-financing seven pilot projects to strengthen the relationship between regional planning and regional development. Overall, a mosaic of different forms and formats is discernible in how each Swedish region develops its own strategy and governance style to pursue regional planning and development.

However, ‘regional physical planning’ (regional fysisk planering) as defined in the Planning and Building Act has only been practised in the Stockholm region and to some extent in the Gothenburg region, and very recently also in the Skåne region, but not across the entire country (Smas/Schmitt 2021, 2022). The reason is that the Planning and Building Act determines specific regions which are supposed to undertake ‘regional physical planning’ rather than making it mandatory across the country. This also means that in principle all regions can apply to become a regional planning authority, but this has to be decided by the national parliament, since it requires an amendment to the Planning and Building Act.

The Stockholm region has a long tradition of regional planning along the lines of this act, as it has produced seven regional plans since the 1950s. For the Gothenburg area, no statutory regional plans have been produced since the 1980s. Due to a change in the legislation in 2019, the Gothenburg region, a sub-regional municipal association within the Västra Götaland Region, lost its formal mandate to produce regional plans in the Planning and Building Act, since regional physical planning must be undertaken by democratically legitimised regions, not by sub-regional municipal associations or similar institutions. Meanwhile, statutory regional physical planning was introduced in the Skåne region in 2019 and in the Halland region in 2023. However, the Skåne, Gothenburg, and Halland regions are also exemplary cases which have practised regional planning over many years by using non-statutory strategic planning instruments to integrate and coordinate regional development and municipal planning issues; a few more regions across the country have done similarly. Nonetheless, it should be noted that regional physical plans, as statutory instruments according to the Planning and Building Act, which currently only exist in the Stockholm and Skåne regions, are ‘non-legally’ binding. As such, they offer municipalities and other planning actors (only) indicative strategic guidelines (à see the fact sheet on the Regional Development Plan for the Stockholm Region 2050 – RUFS).

Municipal level

The comprehensive municipal plan is a statutory plan for land use that should cover all the land and waters within the municipal territory. It outlines the strategic directions of development, informs future decisions and actions by municipal authorities, and should be regularly updated as needed. The comprehensive municipal plan is supposed to outline the course of action the municipality intends to take in its spatial planning in order to align the plan with relevant national and regional goals, plans, and programmes of significance for sustainable development within the municipality (à see the fact sheet on the comprehensive municipal plan for the city of Malmö). In spite of its mandatory status, in contrast to many other European countries, the comprehensive municipal plan is ‘non-legally’ binding, and is only of guiding character for the detailed plans (detaljplaner). In other words, a detailed plan can (in principle) deviate from the comprehensive plan, but in this case the plan must contain an account of how and why it does so. The plan is increasingly used for municipal development programmes focusing on public interests like housing, employment, the environment, and even the well-being of people in the form of social welfare objectives, but in practice there are strong variations across the 290 municipalities in how this instrument is designed (Persson 2020). It is also often complemented or further detailed by other non-statutory plan documents (Fredriksson 2011).

As mentioned above, the county administrative boards ensure that the municipalities comply with the regulations stipulated in the Planning and Building Act and the Environmental Code. They review all comprehensive plans, as well as the detailed plans, with a focus on national state interests, but also advise the municipalities on how to coordinate intermunicipal planning issues, for instance. Even once the comprehensive municipal plan is adopted by the municipal council, the county administrative board has the ability to review the municipality’s decision if it is suspected that national or intermunicipal interests are not sufficiently considered. In so doing, the county administrative boards act as regional advisory bodies for municipal planning, even in the three regions in which regional planning according to the Planning and Building Act is currently practised (namely Stockholm, Skåne, and Halland).

The comprehensive municipal plan constitutes the framework for the development of detailed plans for smaller areas within the municipality. In addition, the municipality may adopt so-called area regulations (områdesbestämmelser) to control land-use planning in relation to certain aspects (e.g. the construction of wind farms) in limited areas of the municipality that are not covered by a detailed plan. Both detailed plans and area regulations are legally binding for authorities and individuals and must be adopted by the municipal assembly. Similar to the comprehensive municipal plans, both detailed plans and area regulations are reviewed by the county administrative board. Detailed plans and area regulations are an executive planning instrument, since they constitute a legal agreement between the municipality and the public or private landowner. They determine and indicate the borders of public spaces, development districts, and water areas. They define the use and design of public spaces for which the municipality is the principal as well as the use of development districts and water areas (à see the fact sheet on the detailed plan for the ‘Mining town park 3, stage 2, part of centre, lower Norrmalm, etc.’ in the municipality of Kiruna).

The aforementioned municipal planning monopoly in Sweden is also underscored by the fact that it is only the municipality which can decide to initiate a planning process. A proposal for a new development can be made by either private actors or by the municipality, but a political decision is needed to initiate a planning process. The plan proposal is developed by the municipal planners, but private consultancy firms are often used to undertake the necessary studies and illustrations. Following this, there is an initial public consultation on the draft plan, which often includes a public hearing. Comments and suggestions on the draft plan are compiled and responded to, and the draft is revised if necessary before it undergoes a second public consultation; the objections and responses are publicly displayed alongside the plan. The plan is to be adopted by the municipal council, but other stakeholders may lodge an appeal in several legal instances.

The Planning and Building Act of 1987 introduced a significant change regarding the initiative in the planning process, which is also related to the significant links between planning and property development. Project initiation was moved upwards in the planning system, i.e. property development projects are now dealt with prior to the adoption of the detailed plan. In other words, existing detailed plans are increasingly used to examine and regulate individual projects before the work on the (revision of the) detailed plan starts. This means that detailed plans are no longer necessarily plans to guide the future building stock; rather, they are used as a first assessment tool for applications for planning permission before the official planning permission is (eventually) granted later on (Kalbro et al. 2012). In addition, today a number of complementary non-statutory planning instruments, such as design programmes or master plans, are used to complement detailed plans (Smas 2022). It is also important to note that land is usually allocated for certain purposes before the detailed planning process starts. This means that the developer is active in the planning process and forms a close partnership with municipal politicians and municipal planning professionals. Development rights are generally awarded based on either the result of a comparison of the tenders submitted by several developers (anbudsanvisning) or are allocated directly without an explicit comparison (direktanvisning) (Caser 2016). A key issue here is land ownership. In Sweden, the national state and the municipalities own a significant amount of land, which underscores the powerful position of municipalities in this respect. However, the overall stock of municipality-owned land varies greatly from municipality to municipality as do the rationales and practices of public landownership, the related land allocation processes, and ultimately the awarding of development rights (Zetterlund 2022).

Figure 3: Planning system of Sweden.

Important stakeholders

| Institution/stakeholder/authority (including webpage) | Special interest/competences/administrative area |

|---|---|

| Swedish Government | Decision-making competence to entrust a regional planning body (§7, 1 PBL= Planning and Building Act). Definition of areas of national interest (see § 3 and 4, Environmental Code). |

| The Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (Boverket) | National public agency that Boverket supervises municipal and regional planning in Sweden from legislative, procedural and architectural perspectives and is responsible for the coordination of the planning instrument “areas of national interest”. |

| Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner) | The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions is an employers' organisation and an organisation that represents and advocates local government in Sweden. All of Sweden's 290 municipalities and 21 regions are members of this association. |

| 21 County Administrative Boards | They supervise the municipal comprehensive plans of the 290 municipalities in Sweden. Of particular interest is the extent to which areas of national interest are addressed. The County Administrative Boards supervise (review) also detailed development plans. |

| Region Skåne | Plan-making competence (according to Planning and Building Act). |

| Region Stockholm | Plan-making competence (according to Planning and Building Act). |

| Region Halland | Plan-making competence (according to Planning and Building Act). |

| Architecture and Civil Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg Architecture Research Group, Lulea University of Technology, Luleå Department of Human Geography, School of Planning, Stockholm University, Stockholm Department of Urban and Rural Development, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala Department of Urban Studies, Malmö University, Malmö Department of Urban Planning and Environment, KTH – Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm Department of Conservation, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg Nordregio - international research centre for regional development and planning, Stockholm |

Research Institutes and University Departments that are either ‘full’, ‘associated’ or ‘affiliated’ members of AESOP – the Association of European Schools of Planning. |

Fact sheets

-

Fact sheet for planning levels_1.pdf (1.09 MB)

-

Fact sheet for planning levels_2.pdf (482.73 KB)

-

Fact sheet for planning levels_3.pdf (1.23 MB)

Attachments

-

Attachment 1: NUTS 3 regions and LAU 2 entities (municipalities) in Sweden in 2016

-

Attachment 2: The formal Swedish spatial planning system (animated image)

List of references

Bohm, K. (1996): Samhällsplanering – erfarenhetsrum och framtidshorisont. In: Olsson, G. (ed.): Poste Restante: En Avslutningsbok. Stockholm, Nordiska institutet för samhällsplanering, 39-44.

Boverket (2017): Regional fysisk planering i utveckling – fyra exempel. Available at: https://www.boverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/dokument/2017/regional-fysisk-planering-i-utveckling.pdf (28 February 2023).

Boverket (2022): Ramverk för nationell planering. Rapportnummer: 2022:05, Karlskrona. Available at: https://www.boverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/dokument/2022/ramverk-for-nationell-planering---slutrapport.pdf (28 February 2023).

Caesar, C. (2016): Municipal land allocations: integrating planning and selection of developers while transferring public land for housing in Sweden. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 31, 257-275.

Emmelin, L.; Nilsson, J.-E. (2016): Fysisk planering – att forma ett ämne. In: Emmelin, L.; Nilsson, J.-E.; Von Platen, F. (eds.): Femtio år av svensk samhällsplanering: vänbok till Gösta Blücher. Karlskrona, 301-322.

Fredriksson, C. (2011): Planning in the ‘New Reality’: Strategic Elements and Approaches in Swedish Municipalities. Stockholm, Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Havs- och vattenmyndigheten (2022): Havsplaner för Bottniska viken, Östersjön och Västerhavet. Statlig planering i territorialhav och ekonomisk zon. Göteborg, Havs- och vattenmyndigheten. Available at: https://www.havochvatten.se/download/18.4705beb516f0bcf57ce1b184/1604327609565/forslag-till-havsplaner.pdf (28 February 2023).

Karlbro, T.; Lindgren, E.; Paulsson, J. (2012): Detaljplaner i praktiken. Är plan- och bygglagen i takt med tiden? TRITA-FOB Rapport 2012:1. KTH: Stockholm. Available at: http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:677565/FULLTEXT01.pdf (28 February 2023).

Nilsson, K. (2018): The history of Swedish Planning. In: Kristjánsdóttir, S. (ed.): Nordic experiences of sustainable planning: Policy and practice, London, 127-137.

Persson, C. (2020): Perform or conform? Looking for the strategic in municipal spatial planning in Sweden, European Planning Studies, 28 (6), 1183-1199.

SCB (2019): Markanvändningen i Sverige – Land use in Sweden. Statistiska centralbyrån, Statistics Sweden: Stockholm. Available at: https://www.scb.se/contentassets/eaa00bda68634c1dbdec1bb4f6705557/mi0803_2015a01_br_mi03br1901.pdf (28 February 2023).

Schmitt, P.; Smas, L. (2019): Shifting Political Conditions for Spatial Planning in the Nordic Countries. In: Eraydin, A.; Frey, K. (eds.): Politics and Conflicts in Governance and Planning. London, 133-150.

Schmitt, P.; Smas, L. (2020): Dissolution Rather than Consolidation – Questioning the Existence of the Comprehensive-Integrative Planning Model, Planning Practice & Research, DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1841973

Smas, L. (2022): Fysisk samhällsplanering på lokal nivå – bebyggelse och markanvändning. In: Bolin, N.; Nyhlén, S.; Oausson, P. (eds.): Lokalt beslutsfattande. Lund, 203-228.

Smas L.; Lidmo J. (2019): Organising regions: spatial planning and territorial governance practices in two Swedish regions. Europa XXI, 35, 21-36.

Smas, L.; Schmitt, P. (2021): Positioning regional planning across Europe, Regional Studies, 55 (5), 778-790.

Smas, L.; Schmitt, P. (2022): Region + planering = regionplanering – en komplicerad ekvation. In: Grundel, I. (ed.): Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid. Svenska Sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi: Stockholm, 42-62.

Solbär, L.; Marcianó, P.; Pettersson, M. (2019): Land-use planning and designated national interests in Sweden: arctic perspectives on landscape multifunctionality, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62 (12), 2145-2165.

SOU (2007): Hållbar samhällsorganisation med utvecklingskraft. Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU 2007:10). Stockholm. Available at: https://www.regeringen.se/49bb39/contentassets/7f73e037630a4ef185a4c6d7ede1a323/hallbar-samhallsorganisation-med-utvecklingskraft-sou-200710 (28 February 2023).

SOU (2015): En ny regional planering – ökad samordning och bättre bostadsförsörjning. Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU 2015:59). Stockholm. Available at: Link is broken, https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2015/06/sou-201559/ seems ok; to be checked by author (28 February 2023).

Strömgren, A. (2007): Samordning, hyfs och reda: stabilitet och förändring i svensk planpolitik 1945-2005. Uppsala.

Zetterlund, H. (2022): The Landed Municipality. The Underlying Rationales for Swedish Public Landownership and their Implications for Policy. Geographica 32. Uppsala, Department of Social and Economic Geography, Uppsala University.